Dear Smithsonian Magazine Editor,

Your October 2019 edition of the Secrets of American History Smithsonian magazine contains an article by David Preston titled “New Evidence Young George Washington Started a War”. The cover image has an illustration by Tim O’Brien of a man resembling George Washington leaning with both hands on a firearm. The body of the article has an additional image by O’Brien showing what appears to be the same figure holding a smoking muzzle loader. The firearms featured in these two illustrations suggest that Washington was carrying a circa 1742 Brown Bess Long Land pattern musket.

Image 1: Two Smithsonian magazine article illustrations of George Washington’s firearm and the 1742 Brown Bess model that the artwork is likely based on

The implication that Washington was carrying a musket during the French Indian war is unfounded and uncorroborated by any historical source and is almost certainly wrong. I would like to correct several misconceptions that the imagery and article imply. The evidence that I will present comes from a combination of historical documents review and the use of Artificial Intelligence image analytics used to evaluate and compare several weapons belonging to Washington to a large collection of period firearms.

The Historical Records

From written records dating to 1755-1772, we can safely establish that Washington owned several long firearms. However, there is no evidence that he used a musket or a fusil. We know this from these sources:

- His diary details his purchase and use of more than one rifle

- His diary details his travels on the frontier with a rifle

- One of his letters indicates that he lent his rifle to another individual during the war and another correspondence suggests that he didn’t ever get it back

- His diary contains entries of his hunting excursions (most likely with a fowler)

- His diary details his use and ownership of a number of fowling pieces

- Multiple letters indicate that Morgan’s rifleman were Washington’s pride and joy unit and attest to his affinity for the military use of a rifle

Image 2: 1956 NRA The American Rifleman Magazine: a review of Washington’s historical firearm collection and the misidentification of the firearm in the Peale portrait as a musket (click image for a larger view)

To emphasize the veracity of these historical records, we can reference the following events:

On July 19, 1754, after a failed expedition to oust the French from the areas of the Ohio River, Washington—the 22 year old commander of the American force—was forced to surrender at Fort Necessity. From the records of the weapons confiscated by the French, we know that there were “7 rifled guns” valued at £6 each.

Nearly two months after his surrender, on August 27, 1754, James Mackay, Washington’s comrade in arms wrote to him:

“I Shall take care that you Shall have your Rifle, but the man that has it hops that youl be So good as to gett him Some other Rifle for it, as you Was plasd to accquaint every person that whatever they Carried Should be their own and every person have payd for what ever they Returnd.”

From the context of the letter, it looks like Washington lent his rifle (not a musket or a fusil) to a soldier during the battle and was now trying to retrieve it.

In another example, Washington’s diary entry for March, 1770 shows that he was staying with his friend Robert Alexander. The two used to hunt together and on that occasion, he rode to “George Town” (a village eight miles upstream from Alexandria, Virginia) to pick up his rifle from the gunsmith John Yost for £6 and 10 shillings (about $1,500 in today’s money). His preference for high quality firearm can be gauged from the fact that during the Revolution, Yost made rifles for American troops and invoiced them at £4 and 15 shillings each. So Washington paid almost a hundred percent premium for this custom-made rifle!

Three years later, on his 41st birthday, February 22, 1773, Washington’s dairy details his purchase of another rifle from Aaron Ashbrook for £4 and 15 shillings. Later that year, he had it repaired by Joshua Baker, a gun-maker in Frederick County, Virginia, who specialized in rifles.

According to the late Milton F. Perry the former curator of history at the West Point Museum, at the time of his death, Washington possessed around 19 pistols, three rifles, four muskets, and nine fowlers. The reason for owning these muskets could be explained through an August, 1748 advertisement published by Washington’s older brother Lawrence. In it, he referred to a runaway slave that stole “new soldier musket”. In similar fashion, it is possible that Washington’s muskets were part of the plantation armory and were used by his staff for site security.

So, from documentary evidence, we have no reason to assume that Washington personally used long firearms other than hunting fowlers or rifles.

Image 3: A sample 75 ¾” long .65 caliber fowler circa 1750-1760 (George C. Neumann Collection Valley Forge National Historical Park)

Caliber and Powder Charge

One possible reason for Washington’s use of longer custom made firearms with smaller calibers (i.e. less than .75) can be attributed to the American emphasis on ball speed and distance. In Europe, hunting with guns was a luxury pastime reserved for the nobility. In America, on the frontier settlements, gun powder and lead were scarce and gun ownership and hunting skills were a matter of survival. Children were introduced to firearms from an early age. Reverend Joseph Doddridge who grew up on the Virginia frontier wrote:

“A well grown boy, at the age of twelve or thirteen years, was furnished with a small rifle and shot pouch. He then became a fort soldier, and had his port hole assigned him. Hunting squirrels, turkeys and raccoon soon made him expert in the use or his gun…

Shooting at marks was a common diversion among the men, when their stock of ammunition would allow it; this, however, was far from being always the case. The present mode of shooting off hand was not then in practice. This mode was not considered as any trial of the value of a gun; nor, indeed, as much of a “test of the skill of a marksman. Their shooting was from a rest, and at as great distance as the length and weight of the barrel of the gun would throw a ball on a horizontal level.

Such was their regard to accuracy, in these sportive trials of their rifles, and of their own skill in the use of them, that they often put moss, or some other soft substance, on the log or stump from which they shot, for fear of having the bullet thrown from the mark, by the spring of the barrel. When the rifle was held to the side of a tree for a rest, it was pressed against it as lightly as possible, for the same reason. Rifles of former times were different from those of modem date; few of them carried more than forty-live bullets to the pound. Bullets of less size were not thought sufficiently heavy for hunting or war.”

Another American innovation was the reduction of bullet caliber: the Brown Bess smoothbore army muskets averaged .75 of an inch. Many Pennsylvania long gun makers reduced the caliber to between .45 and .50. The smaller rounds made for major savings. Using one pound of lead, one could mold about 11 .75 caliber balls; for a .50, that figure would triple to 33.

The Europeans believed that a larger bullet was more lethal than a smaller one and so refused to downgrade the size of their rounds. It turns out, though, that the size of the round does matter, but the bullet’s lethality depends to a larger degree on the proportion of gunpowder charge to the size of the bullet. The American practice was to load half the weight of the bullet in powder.

Alexander Rose, in his excellent book: The American Rifle, explains this practice in the following way:

“[Using this ratio, an American smaller ball weighing 200 grains (1 gram = 15.43 grains) would be boosted by 100 grains of powder (6.5 grams), and a British ball of 400 grains, by the same 200 grains. Thus, a British shooter would load the same amount of powder as an American, but because the ball was much heavier, each grain would be forced to do more work. The projectile’s velocity and kinetic energy consequently suffered. So, what the smaller American ball lost by its lack of weight was made up by increased velocity of the higher powder ratio.]”

Imagery of Washington’s Long Firearm

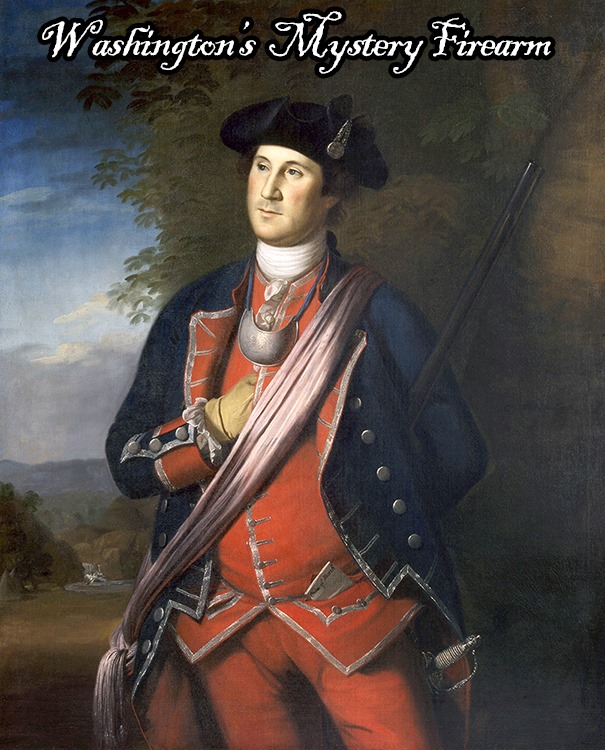

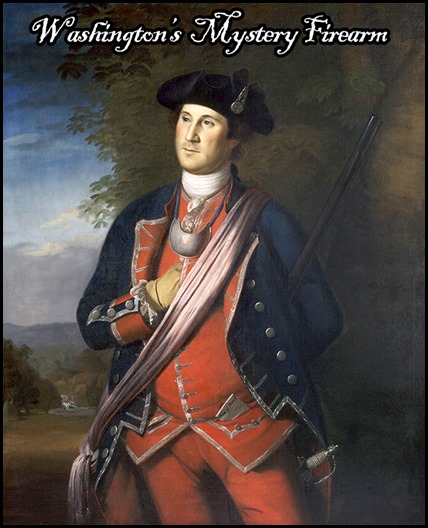

Peale’s portrait of Colonel Washington is unique among the many paintings of eighteenth-century American field officers who are typically depicted with swords and not with long firearms.

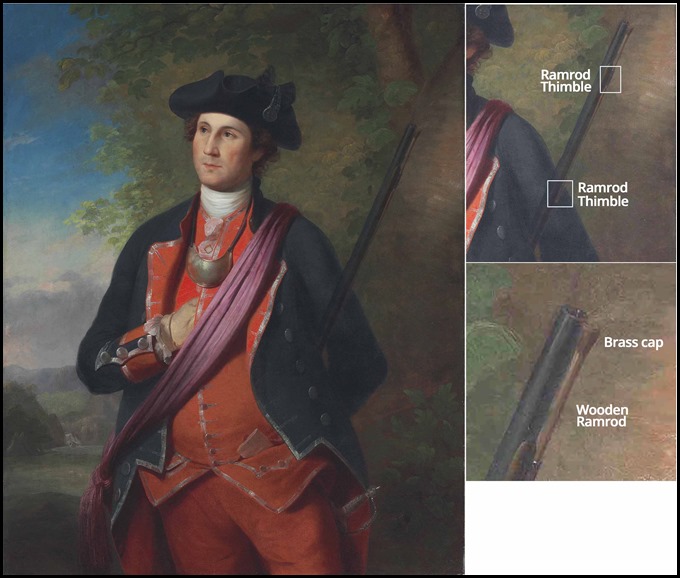

Image 4: The 40 year old Colonel George Washington in 1772 depicted by Charles Willson Peale. The painting shows a non-standard issue firearm that does not match any known Brown Bess musket or fusil pattern

Image 5: Two Engravings of George Washington by Forrest John 1814-1870 after the portrait by Charles Willson Peale 1772. The slender stock, the ramrod thimbles, and the lack of a bayonet lug suggests that this a rifle or a fowler.

One example of this trend is the 1821 painting by John Trumbull titled the “Surrender of British General John Burgoyne at Saratoga”. The group painting only shows two firearms: one a short carbine carried by Captain Seymour (the figure on horseback), and the other a long firearm held by Colonel William Prescott. Colonel Morgan—the rifle icon standing in front of Prescott in a white linen hunting frock—is seen holding a sword. Evaluating Prescott’s long firearm in this painting suggests that this is also not a Brown Bess. Prescott was over 6 feet tall and from the proportions and height of the firearm in the image (the tip of the barrel reaches his mid face) it looks like his gun could possibly be a fowler or a rifle.

Image 6: The 1777 painting depicting General Burgoyne prepared to surrender his sword to General Gates (see painting legend here)

Prescott owned a sword and we have evidence that he used it during the Battle of Bunker Hill, so the fact that he is featured in the painting with a rifle (likely Morgan’s) must have had some significance.

The shortage of long firearms in group and personal portraits of senior American officers likely has to do with the subtle message that the subjects of paintings wished to convey. The presence of edged weapons such as the small sword or cavalry saber indicated military status and rank. Firearms were utilitarian tools. Throughout history, guns were associated with common soldiers and weren’t usually carried by officers in the field. The only time a gentleman officer looked through the sights of such weapons and pulled the trigger was when he was engaged in target practice or hunting.

Washington is probably one of few senior American or British officers who had such an affinity for long firearms and would thus prefer that it be incorporated into his portrait.

Image 7: Plenty of swords but not one firearm in sight. The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, October 19, 1781, by John Trumbull c.1820 (see painting legend here).

Alexander Rose provides the following explanation for Washington’s inclusion of a long firearm as a prop in his portrait:

“The rifle is instead discreetly tucked away in the background, serving, it seems, as a reassuring symbol, for those in the know, that this individual, dressed in a uniform last donned two decades before, is one of them. So what was Washington telling his fellow Americans? The answer lies hidden somewhere amid the vast, remote American wilderness, An unconquered territory densely thicketed by forests, rumpled by towering mountain ranges, and watered by unbridgeable rivers.

For newcomers to this land, it was a terrifying place such as had not existed in Europe since the dark and cold days of the Neanderthals. It was the frontier… In the 1770s, for those staid Virginian planters sitting in the clubby House and reluctantly steeling themselves for the final showdown with London that would erupt at Lexington and Concord, that rifle in the Peale portrait symbolized something meaningful. Washington’s rifle was carefully calculated to prompt a certain reaction. It was a deliberate effort to capture the image of the frontiersman, then as now a halcyon icon of very American—or in the political context of the 1770s, anti-British—traits: doughty individualism, rugged self-reliance, and an independent spirit determined to defend hearth and home against the predations of outsiders.

By identifying himself simultaneously with the American frontiersman and with the professional soldier, Washington succeeded in squaring an obstinately round circle. One day, and that day was fast approaching, this feat would Lead to his unanimously approved elevation to commander in chief of the American forces for a war of independence.”

So, based the social trends of the time and the preference for personal arms found in the period paintings, we have no reason to assume that an American officer would carry a Brown Bess musket.

Image 8: Portraits of revolutionary war officers (both British and American) posing with swords

The Analysis of Washington’s Firearm

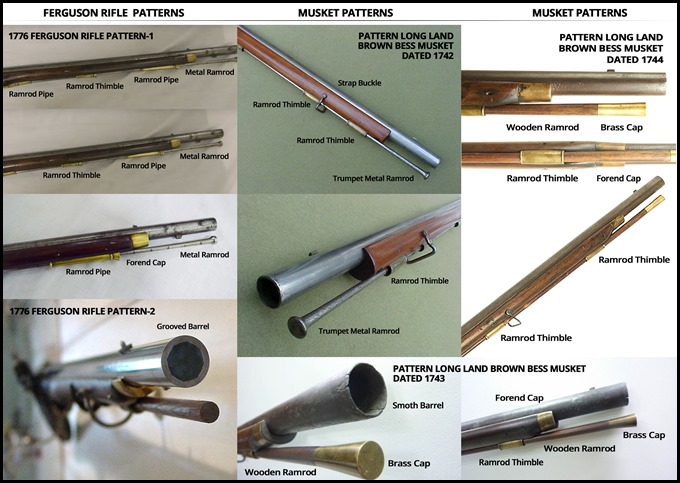

Considering the previous historical and artistic evidence, I will argue that the firearm in the painting is not a standard military issue Brown Bess (as depicted in the Smithsonian article), but rather a custom made piece, most likely a rifle or a fowler. Fowler or fowling arms were primarily used for hunting waterfowl during the 17th and 18th centuries. We know from historical records and museum specimens that these type of firearms saw action during the French Indian War and during the American Revolution with militias. The fowler was operationally similar to the musket but had a smaller caliber, was longer, and didn’t have a bayonet lug.

My argument that the firearm in the Peale painting is a rifle or a fowler is supported by the the following:

- The key features of the firearm in the painting and several later lithographs of it do not match any known Brown Bess morphology.

- The edge of the wood stock closer to the barrel tip doesn’t have a foreend brass cap. It just tapers upwards toward the barrel.

- The tight fit of the ramrod next to the barrel doesn’t leave room for mounting a bayonet–which was a mandatory feature on the land pattern Brown Bess

- The diameter of the brass ramrod cap is close to the caliber of the barrel. This was not the case with the Brown Bess where the ramrod cap was noticeably smaller than the 0.75-0.76 range caliber

- The length of the firearm is about 65”-70”, much longer than the average 58” of the Brown Bess

Note on Firearm Uniformity

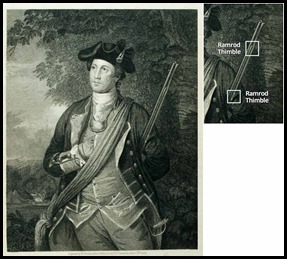

There are numerous variations in the models of 18th century military firearms. Individual items like the ramrod composition (wood/brass/steel), the use of belt hooks, the geometry of the stock and thimbles could be different for each production batch by the same gunsmith. There is a great deal of variation among samples of surviving firearms, even from the same year and shop. These differences are the result of not just eighteenth-century manufacturing processes but also deliberate choices made by individual gun makers and the incremental evolution of the firearm design.

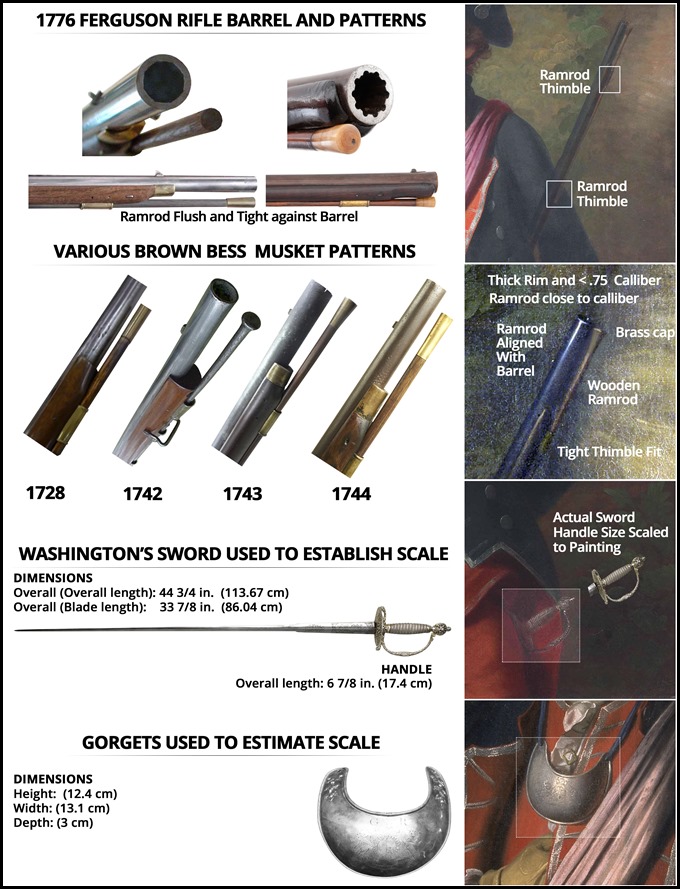

Image 9: Two Brown Bass musket patterns from c. 1755 and two c. 1776 Ferguson rifle patterns

The Analysis

My strategy in trying to solve the question of Washington’s firearm involved the use the process of elimination. The rationale was that it would be exceedingly difficult—if not impossible—to precisely match the firearm in the painting, but relatively easy to eliminate the possibility that it was a Brown Bess.

My first objective was to collect precise dimensions from the actual portrait and from at least one item depicted in it and then to try and determine the scale of the painting in order to confirm the accuracy of Peale’s rendition of the details. Once the scale was determined, I evaluated the caliber of the firearm muzzle: if it came up in the 0.75 range, then it could be a Brown Bess. Anything significantly below that caliber would indicate a rifle or a fowler.

The second objective was to evaluate the overall length of the firearm. The Brown Bess standard length of the long land pattern was about 58”, so a length in excess of 60”-70” would eliminate the possibility that this was a standard pattern musket.

Image 10: Samples of several Brown Bass patterns used in the analysis

In addition to solving the painting scale problem, I also used an object detector/classifier to evaluate a large collection of images of period firearms. This was done in the hopes of finding a match or at least a close similarity.

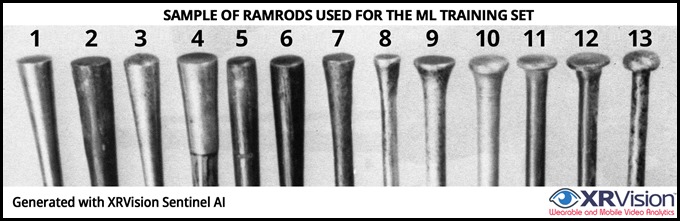

Image 11: Sample of images of ramrods used for the machine learning training set

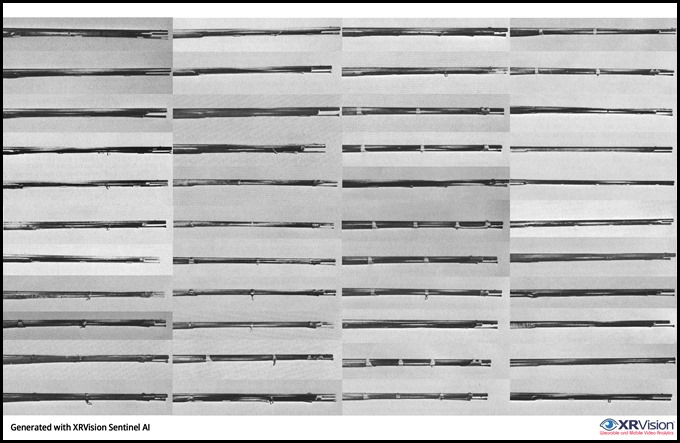

Image 12: Sample of several hundred images of period long firearms used for the machine learning training set

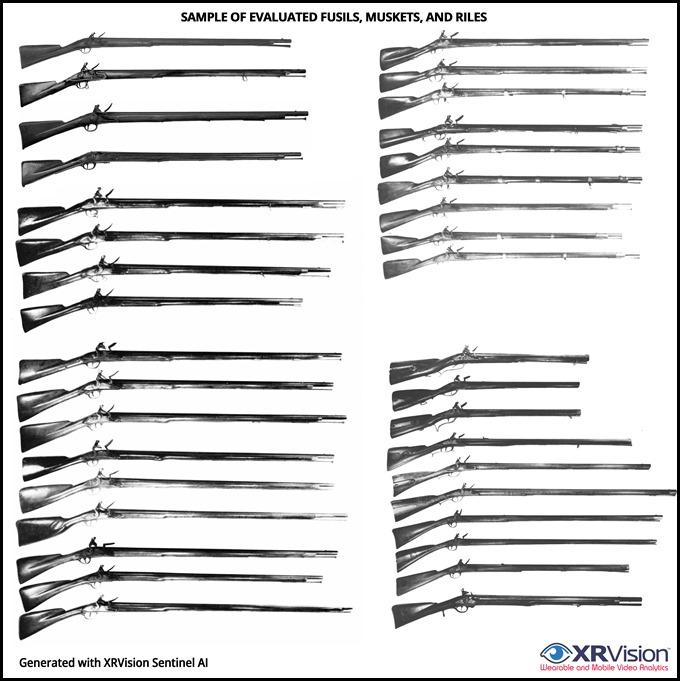

Image 13: Sample of several hundred images of period long firearms evaluated in the analysis

Solving the Scale Problem

Luckily, both Washington’s portrait and his small sword survived and are kept at the Mount Vernon Museum in Virginia. The curators at the museum were exceedingly generous and accommodating and allowed me to visit and take precise measurements and high resolution scans of Washington’s small sword. I was also fortunate enough to acquire a high resolution scan of the restored Peale portrait.

Image 14: Various objects and their rough scale in Peale’s painting

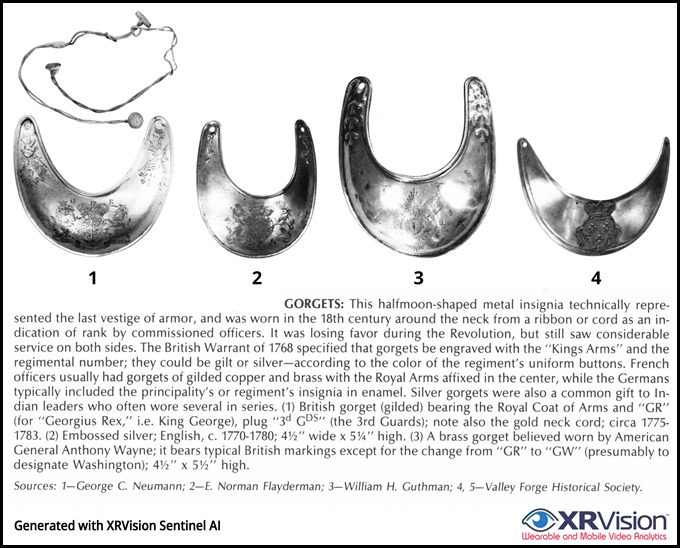

Image 15: Collection of gorgets used for size estimation

After collating the field measurements, I then dimensioned all of the visible parts of the small sword in the portrait. I focused on the ornaments, and details on the quillion, grip, knuckle guard, pummel, and button.

Image 16: Dimensions taken directly from Washington’s short sword: courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Measurement Results

The analysis of the physical sword dimensions and its comparison to the sword depicted in the portrait indicate that Peale’s work was accurate to within 2 mm. This is quite incredible and a true testament to Peale’s artistic genius.

Washington was about 6’-2-6’-3” (74”-75”) and as can be clearly seen in Peale portrait, the firearm—if rotated from slanted to vertical view—would be slightly shorter than his height. Using the paint scale vs. the actual scale, I concluded that the firearm caliber was in the range of .65 caliber and the firearm length was in the range of 70”. As I suspected, the caliber was about 10% smaller than that of the Brown Bess, .75, and about 20% longer of the Brown Bess 58”.

Image 17: Projected length of gun using the scaled firearm and John Trumbull’s portrait dimensions for Washington’s body

Based on these evidence, I think that we can conclude that the firearm in the Peale portrait is not a Brown Bess and neither should it be depicted as one in the Smithsonian article.

Credits

Special thanks to Mrs. Amanda Issac, the Associate Curator at the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association for allowing me to photograph and take measurements of George Washington’s 1767 Silver-Hilted Smallsword. Credit: Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Special thanks to both Mrs. Rebecca Williams, the Museum Operations Assistant and Mrs. Patricia Hobbs, the Associate Director/Curator of Art & History Museums at Washington and Lee University for sharing a high resolution image of the portrait U1897.1.1, titled “George Washington as Colonel of the Virginia Regiment” (1772) by Charles Willson Peale. Credit: Washington and Lee University.

Special thanks to Mr. Less Jensen, the Curator of Arms and Armor at the West Point Museum for allowing me to photograph and measure the historical arms at the museum’s special collection. Credit: U.S. Army West Point Museum

References and Sourcing

XRVision Sentinel AI Platform – Image reconstruction and object classification

Washington’s Height

Various sources have put Washington’s height between 6 ft and 6 ft 3.5 in. See: Chernow, Ron, Washington: A Life, 2010, The Penguin Press HC ISBN 1-59420-266-4; Wilson, Woodrow, George Washington, 2004, Cosimo, Inc., p. 111; Alden, John Richard, George Washington: A Biography, 1984, Louisiana State University Press, p. 11; Lodge, Henry Cabot, George Washington, Vol. I, 2007, The Echo Library, p. 30; Haworth, Paul Leland, George Washington, Kessinger Publishing, 2004, p. 119; Thayer, William Roscoe, George Washington, 1931, Plain Label Books, p. 65; Ford, Paul Leicester, The True George Washington, Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott Company, 1896, p. 18-19

Bibliography

American Rifle: A Biography – Alexander Rose

Men of War: The American Soldier in Combat at Bunker Hill, Gettysburg, and Iwo Jima – Alexander Rose

Notes on the settlement and Indian wars of the western parts of Virginia and Pennsylvania from 1763 to 1783 – Joseph Doddridge, p123

Firearms in American History 1600-1800 – Charles Winthrop Sawyer

The History of Weapons of the American Revolution – George C. Neumann

The Flintlock Musket: Brown Bess and Charleville 1715–1865 – Stuart Reid, Steve Noon (Illustrator), Alan Gilliland (Illustrator)

Red Coat and Brown Bess – Anthony D. Darling

Red Coat & Brown Bess. Historical Arms Series No 12 – Anthony D. Darling

The Brown Bess; An Identification Guide and Illustrated Study of Britain’s Most Famous Musket –Erik Goldstein, Stuart Mowbray

Thoughts on the Kentucky Rifle in its Golden Age 3rd Edition – Joe Kindig Jr.

Firearms in American History – 1600 to 1800 – Charles Winthrop Sawyer

The Pennsylvania-Kentucky Rifle – Henry J. Kauffman

Kentucky Rifles & Pistols 1750-1850 – James R. Johnson

Founders Online – Correspondence and other writings of six major shapers of the United States

George Washington’s Gorget

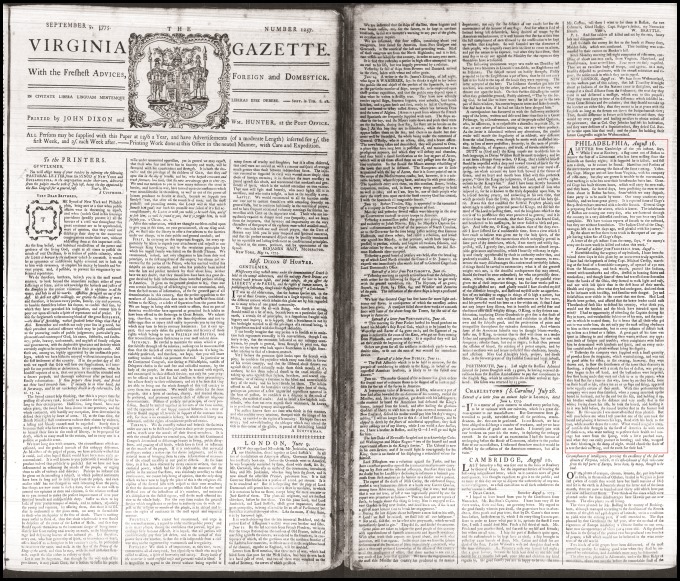

Image 18: The Virginia Gazette Saturday September 9, 1775 discussing Captain Morgan’s and Captain Cresap’s rifleman arrival to Boston (click image for larger view)

Henry and John Yost Gunsmiths (Samuel Preston Adams IIINSSAR# 185382 Saramana Chapter SAR)

“John Yost, arms supplier, Georgetown, District of Columbia. On July 7, 1776, of that year he contracted to make 300 muskets at £4/5/0 each, and 100 rifles at £4/15/0 each. By the late summer of 1776 he had erected a horse mill for boring gun barrels in Georgetown, now in the District of Columbia.

On January 17, 1776, the Council of Safety requested information on furnishing and delivery of guns. On August 1, 1776, the Council of Safety concerning shipment of arms. On September 13, 1776, Yost wrote to the Council of Safety concerning the manufacture of guns.

On December 9, 1776, Yost wrote to the Council of Safety requesting monies. In 1776 Yost wrote to the governor, asking for payment on account for making muskets and rifles. [Maryland State Revolutionary War Papers]. On 10 August 1776, the Council of Safety paid “John Yost ,400 to enable him to manufacture good substantial Musquets” [5 Amer Arch 1 at 1352].

On 3 March 1776, “Pay to John Yost £2/11/7 for repairing guns” [11 Md Arch 214]. On 23 May 1776, “Send the Musquets made by John Yost at Georgetown to Port Tobacco in Charles County” [4 Amer Arch 5 at 1576]. John Murdock of Montgomery County to the Governor: “16 July 1781 “John Yost who has already repaired several public arms and is now employed about those you sent last to this county.” Murdock warned the governor that unless Yost was paid for work already done, and the state was much in arrears, he was going to stop work [47 Md Arch 351-52].

During the War of American Independence, John and his brother Henry Yost of George Towne (now Georgetown, Washington, D.C.) manufactured muskets and bayonets for the American forces. Henry (Heinrich) and John (Johannes) Yost (Youst) entered into contract with the Revolutionary Committee of Safety as early as October 1775 to produce muskets and bayonets exclusively for the Continental Congress for one year. They committed themselves to delivering to Annapolis 75 muskets with bayonets by May 1776. But they ran behind, and by May 1 the weapons had not yet arrived in the capital of the Province of Maryland. Therefore, they received a letter admonishing them. They then committed themselves to producing not only the 75 weapons by May but to deliver an additional 25 each following month to Major Price of Georgetown.

They must have completed the first order by May 23, because Col. Beall was told on that day to deliver muskets produced by John and Henry Yost to the company stationed in Port Tobacco on the Potomac.”

George Washington to Daniel Morgan, June 13, 1777:

”Orders to Colonel Daniel Morgan [Middlebrook, N.J., 13 June 1777]

Sir

The Corps of Rangers newly formed and under your Command, are to be considered as a Body of Light Infantry and are to act as such, for which reason they will be exempted from the common Duties of the Line.

At present you are to take post at Van Veighters Bridg⟨e⟩ and watch, with very small scouting parties (to avoid fatiguing your men too much under the present appearance of things) the Enemy’s left Flank, and particularly the Roads leading from Brunswic towards Millstone, princetown &ca.

In case of any movement of the Enemy you are instantly to fall upon their flanks and gall them as much as possible, taking especial Care not to be surrounded⟨,⟩ or ha⟨ve your⟩ Retreat to the Army cut off.

I have sent for Spears which I expect shortly to receive and deliver to you, as a defence against Horse. Till you are furnished with these, take care not to be caught in such a Situation as to give them any advantage over you.

Given under my Hand at Head Quarters Middle Brook this 13th June 1777.”

Copyright 2020 Yaacov Apelbaum, All Rights Reserved.

Nothing short of amazing.

Thank you for the kind words Nina.

Exactly Nina. Yaacov has an AMAZING propensity for clarity, informative detail and the rigor of wanting… no… NEEDING… to ‘get it right’. When he sees or hears something that just isn’t ‘right’- he will sometimes go to excruciating effort and detail to strive to ‘right the wrong’. Not only is the man here very intelligent, he has (almost, as in no one ever truly does) mastered the rapidly dwindling art of written prose. I ALWAYS learn- sometimes a LOT- when I read his articles here. Toda, yet again, Yaacov!!!

Thank you for the kind words my friend. G-D bless.

Yaacov Apelbaum, I always enjoy your work. It is always interesting to me how you identify a problem, use your intelligence and skills and the analytics (I can only dream of understanding) to solve puzzles, i.e., efforts of domestic terrorists to damage our country, or a man like Preston who appears to want to sully our first president’s reputation (though, to be honest, I don’t know his motivation — but the title of his article or work indicates a negative slant; and having read Washington is now criticized for being a slave holder, I guess critics will attack any facet of his character in order to degrade our first president or this nation’s founding fathers.) Thank you for your interesting work. Someday you must write a biography. I always wonder about your childhood, parents, upbringing, and life, and what has brought you forward as a great patriot.

Thanks for the articles,

Joan

Thank you for the kind words Joan,

Writers like David Preston (who BTW, is a professor at the Citadel) are a part of a wide-scale ‘progressive’ penetration into American colleges, museums, and public organizations like NPR that effects professors, administrators, and boards of trustees who act as enablers and promoters for this statue removing, city and state renaming style propaganda.

I think that the reasons for the attacks on the founders are that by disparaging them, they can then deliver their ultimate agenda of delegitimizing the founding principles of our nation.

One example of this trend is the case of 2nd Lt. Spenser Rapone. The administrators at West Point knew that he was an avowed communist and held Marxist anti-American beliefs. They also know about his insubordination and extremist on-line activity as early as 2015. But, despite his conduct, the U.S. Military Academy’s administration allowed Rapone to graduate in 2016.

So, Preston is not a lone voice in the wilderness. Retired Army Lt. Col. Robert Heffington, a former professor of history at West Point, described this phenomena in detail in an open letter in 2017.

Yaacov Apelbaum, Thanks for the article. You are a asset to the USA. I have tried to get someone to comment on something but I get no where. If you would just give a one sentence comment if I am missing something I would appreciate it. Here goes.

The best weapon we have against China is Computer Chips. The 5 or so countries that make them (China does not) made a treaty to declare them National Security risk items and limited or stopped the sale to China they would be brought to their knees in a short time.

This may be said better or worked differently but we hold the cards. Is this out in left field?

P.S. Did you have lunch with that author yet? Just though he wanted you to go this month.

Sorry Yaacov, I put this comment under the wrong article. I went past the WHO article accidently.

Not a problem. You can either move the comment to the right post or leave it here.

Thank you for your kind words.

Yes, computer chips are one key area that we can/should leverage against China. But there is a long list of other technologies/industries that we should urgently block China from deploying. A few examples are:

5G Networks

Drones and other autonomous technologies

AI technology

Imaging, cameras and IoT devices

Nano Technology

BioMedicine like Gene Therapy and Cloning

Quantum computing

We should also immediately adopt a much more aggressive approach to Chinese IP theft and on-going hacking against our industrial and government targets. State-sponsored IP theft should be treated as a criminal matter. In this regard, we should stop all Chinese student exchange programs and terminate their visas. There is no reason why the Chinese should be getting their PhDs in our leading research institutions. Also, when a large number of ivy league professors/administrators get paid by China to sponsor and host pro-China events, they should be persecuted and given stiff sentences. The same applies to the Chinese influence operations through our own MSM. Media outlets that are caught supporting/enabling these operations should be heavily fined/lose their broadcast licenses, and their senior management and BoD should be prosecuted individually.

Finlay, there is no reason why factories across the US should continue to crumble into dust, all while we pay China to building dozens of new ones every year and send their output back to the US. China is a hostile communist state that created the ‘Nuclear North Korea problem’ and continues to use it against us. We should always remember that their ultimate ideological objective is not to find a way to coexist with us, but to destroy and dominate us.

This is a fantastic write-up. Always enjoy your articles.

Thanks you shawntothebee for your kind words.

Please contact me about your citing of Capt Thomas Youngs Seymour at the surrender of Saratoga. Your work is excellent. sh2ldhq@erols.com

Thank you for your kind words Captain Tarantion.