The idea for the password survey came about more than fifteen years ago when I managed a security team in a large Fortune 500 organization. While designing a new fraud detection platform, we discovered that many previous security incidents were attributed to compromised user passwords and credentials. The data suggested that this problem affected all business divisions and departments across the company and our partners. After a successful campaign to launch a corporate-wide root cause initiative, we ran a pilot that examined password storage and retrieval practices in one of our regional offices with about 900 employees. After concluding the initial survey, we expanded the sampling to three other corporate locations.

The results of the first survey were supplemented by data I collected a few years later while working for a managed security service company that provided hosted proxy, firewall, IDS, and anti-malware service to several hundred credit unions and community banks. The focus of the second survey was on small to medium size US-based financial institutions.[1]

The total population examined in the study was about 3700 accounts and individuals. The corporate units included development, IT administration, business groups, and general staff. The sampled data reflects a typical cross-section of large (20K-40K) and small to medium (20-750) sized organizations and represents a historical snapshot of password practices in a typical regulated financial service company circa 2003-2010.

Chart 1: Password found by business unit

Background

Knowledge-based authentication that utilizes passwords differs from other access control methods because it promotes the idea that by increasing password entropy, we can resist and discourage a brute-force password recovery attack.

For many security practitioners, this seems like a panacea. Policies calling for additional password complexity appear attractive initially, but their practical enforcement on a multi-platform and enterprise-scale is challenging.

This is especially true when we prohibit users from writing down or reusing passwords. The user’s inability to manage numerous complex and frequently expiring passwords can eventually compromise even the most secure environments that support multi-tiered firewalls and utilize the most advanced IDS and robust VPN connectivity.

Paradoxically, it seems that when it comes to passwords, the user is caught between a rock and a hard place; the more secure the password, the less so the user.

Heterogynous Environments and a Glut of Passwords

The never-ending cycle of M&A continues to create heterogynous platforms within the enterprise. This phenomenon results in the proliferation of systems with different rules for password lifecycles, login procedures, and authentication standards. The impact on users has been overwhelming, as they must deal with an ever-increasing number of login challenges.

Even in well-consolidated enterprises that utilize state-of-the-art Active Directory and Single Sign-On, there are a handful of work-issued standalone devices and online accounts that are not tied to the central login infrastructure. Even in these integrated environments, the expiration of individual passwords is rarely synchronized, often causing a cascade of resets on other systems with user lookouts and loss of productivity.

To further complicate this, all employees also maintain dozens of non-work-related passwords that they use during their work day. This significantly increases their cognitive burden, so to conserve energy, some resort to consolidating their private and work passwords into a single file. The survey suggests that if we tally the work and private accounts, the average number of user passwords each person has can exceed 60 (Chart 2).

The number of work-related accounts varied with the user’s corporate responsibility (Chart 3), but on average, each had 10-20 passwords.

Information Overload

The human factor plays a significant role in creating, storing, and retrieving complex passwords. Several psychological experiments have demonstrated that subjects can repeat accurately around eight meaningful combinations of letters, numbers, and words.[2]

When users are given several random eight-character passwords, most will remember only one. If they are required to remember two or more such passwords, they will likely resort to writing them down.

When asked how many IDs and passwords they had to keep track of, the user immediately answered, “Way too many!” Most users also stated that it was bad enough when they only needed a handful of passwords to access e-mail, the network, and mainframe accounts. But now, every internal and external application requires a complex password.

Chart 3: Average number of passwords per user type

Chart 4: Reasons for writing passwords down

So how did the users resolve the problem of maintaining dozens of strong passwords? When pressed, most admitted—as the research suggested—that they resorted to keeping a written list or that they have been using the same password or a variant of it for multiple systems.

On the record, administrative staff denied that they followed this practice, but off the record, they admitted that they were powerless to stop it and that they were guilty of these same offenses. Other industry sources suggest that this is indeed a widespread phenomenon.[3]

When questioned about their memorization techniques (the policy requires that passwords be memorized), many of them indicated that utilizing mnemonics, backronym, and other techniques was tiresome and this resulted in forgetfulness, mistakes, and system lockouts.

Most users (75%) stated that they could not memorize complex passwords, and when they attempted to achieve this in the past, it always resulted in password resets. It is interesting to note that as many as 10% of the users felt that the high frequency of password expiration did not warrant the investment in memorizing it. Another 10% of the users felt that writing the password down made them more productive.

Chart 5: Password issued vs. password memorized

Password Storage Strategies

The password searches identified two types of password storage strategies. The first group (1), which consisted of 27% of the recovered passwords, was made up of data that was either handwritten or printed and stored in the user’s immediate work area.

The written documents included artifacts such as post-it notes, legal pads, notebooks, and text on dry-erase boards. The second category (2) consisted of 73% of the recovered passwords found on electronic storage in digital files on portable storage devices, PDAs, phones, hard drives, and network shares.

Chart 6: Password storage areas

The large percentage of electronically stored passwords suggests that users are somewhat security conscious. They do look for the middle ground between keeping passwords out in the open and memorizing them.

The high rate of spreadsheet utilization (35%) for password storage suggests that without a proper company-sponsored tool for managing passwords, like a password safe, users will instinctively gravitate toward the next ‘best’ technology available in-house.

Password Hangouts

The majority (5% each) of users hid passwords either under a mouse pad or on sticky notes that were kept in a book or folder somewhere in the user’s immediate work area. The total percentage of passwords hidden ‘under’ various items (Table 1) was 27%.

|

Password Locations Office Work Area |

# Found |

% of Total |

|

Under the mouse pad, stapler, or tape dispenser |

174 |

5% |

|

Under keyboard |

86 |

2% |

|

Under desk calendar |

77 |

2% |

|

Under flower pot |

32 |

1% |

|

Under garbage can |

11 |

0.3% |

|

Under printer |

29 |

1% |

|

Under phone or phone reference card |

51 |

1% |

|

Under carpet or mat |

7 |

0.2% |

|

Under bookshelf |

38 |

1% |

|

Under paper tray |

30 |

1% |

|

Under or on a whiteboard or clipboard |

61 |

2% |

|

Under a trivet, coaster, paperweight, or pencil holder |

18 |

0.5% |

|

Interior door of coat cabinet |

18 |

0.5% |

|

A sticky note on the monitor |

40 |

1% |

|

Note inside a book or wallet |

180 |

5% |

|

Note in a music CD box |

67 |

2% |

|

On the whiteboard, obfuscated using letter or number padding |

72 |

2% |

|

Total |

1058 |

27% |

Table 1: Hidden password locations – Office work area

|

Password Locations on Electronic Storage |

# Found |

% of Total |

|

On floppy disk inserted in the drive |

15 |

0.4% |

|

On USB, flash drive, or other device |

80 |

2% |

|

Protected spreadsheet on a password-protected network share |

613 |

17% |

|

MS Access database on a network share |

216 |

6% |

|

Spreadsheet on a network share |

620 |

17% |

|

Text files located on a network share |

281 |

8% |

|

e-mail file (the user would create an e-mail himself the new password) |

408 |

11% |

|

MS Word document |

103 |

3% |

|

File stored on an Intranet website |

300 |

8% |

|

File stored on an Internet website |

26 |

1% |

|

Total |

2662 |

73% |

Table 2: Hidden password locations – Electronic storage

The majority (73%) of the hidden passwords were kept on electronic storage (spreadsheets, documents, and e-mails) on a variety of locations, the most common being (1) 34% on network drive, and (2) 11% on the e-mail server (Table 2).

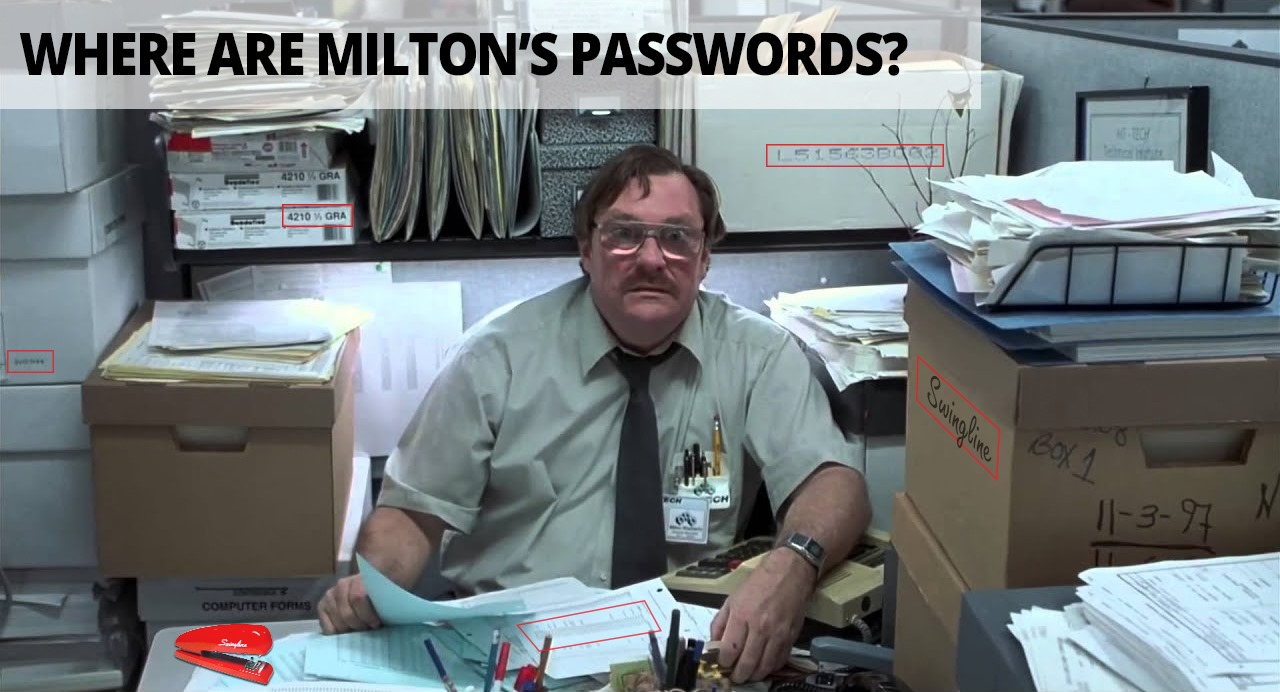

Only 1% of the users openly placed the latest password on their monitor (Figure 1). It is interesting to note the password generation algorithm used. The first password on the list (which was complex) was used as the seed for all future passwords permutations. Each time the system required a new password; the user wrote the new one down and erased the previous one.

Whenever the system permitted the re-use of old passwords, we found a high degree of password recycling via password variances and sequential use. This included 62% of developers, 86% of administrators, 97% of business users, and 94% of admin and facility staff.

Figure 1: User passwords written on a sticky note

Is there a Method in the madness?

75% of the users cited poor memory as the main reason (1) for writing and hiding passwords. The second (2) reason cited was the unspoken legitimacy of this practice and its widespread use. The third (3) reason was that several users shared the password, so having it written in a central location was the most convenient way to synchronize it and keep all users informed of any changes. This was primarily the case amongst DBAs, system administrators, and developers (87% combined). The majority of interviewees also acknowledged that they were aware of existing security policies that clearly discouraged such practices.

From conversations with administrative staff, ignorance of the law was not a factor in writing down passwords (Chart 8). Over 90% of the admins acknowledged that they knew that writing down their system passwords was against policy and information security directives, but they did it because they were located in a physically “secure area” with strict access controls and that it was a calculated risk.

Chart 7: Percent of administrators told not to write down passwords

An interesting usage relationship shows that systems that periodically require users to change passwords trigger more people to ‘hide’ them in written form near their workstations. We estimated that the likelihood of finding written passwords near a workstation subjected to frequent password changes was 35% to 55%. At the same sites, the likelihood was only 10% to 20% for workstations connected to systems that did not enforce frequent password changes.

In many cases, over a third of the users created sequential passwords (Chart 8), such as changing Pa$$w0rd_1 to Pa$$w0rd_2. The stats for administrative users show that this practice was higher than 80% when permitted by the system. This information, again, is confirmed by other studies that show the user’s tendency to avoid constantly memorizing new, complex passwords and writing them down.[4]

Chart 8: Used sequential passwords

Social Factors that Contribute to Password Mismanagement

Password security relies on the premise that passwords are kept secret at all times. This is not a trivial requirement because in a typical password life cycle, there are many opportunities for compromise whenever a password is created, used, transmitted, or stored. Passwords are always vulnerable to compromise because:

- They need to be initially created and assigned to a user

- They need to be transmitted

- They need to be changed

- They need to be stored and retrieved

In this context, sharing passwords among users would eliminate the need to keep it secret. When we asked the users about sharing passwords, the unanimous response was that this was a common practice exercised by all. The system and database administration and InfoSec teams, which should have led the charge in fighting this phenomenon, were the most significant practitioners of group password sharing (Charts 9-10).

Chart 9: Password sharing among administrators

Chart 10: Password sharing among developers

This contradictory situation raised several questions. When we asked the users about the prohibited practice of password sharing, they provided the following rationale:

- Friendliness: Users try to avoid behavior that would put them in a negative social light. Individuals who strictly protect their passwords by steadfastly refusing to write them down or share them with colleagues can be seen as anti-social.

- Conformity: Due to the strong emphasis placed on “being a team player” and the importance of collaboration, many individuals determine that conformity is important and work hard to be sure that others see them as easygoing and trustworthy. For example, if a system administrator (an authority figure) asks a user for his login password, he will likely reveal it because he doesn’t wish to seem suspicious of an authority figure.

- Trust: Sharing passwords between team members can be seen as a sign of collegial affiliation. If a user refuses to share a password with a co-worker, especially where such practice is commonplace, it could be seen as a sign of distrust.

- Unwritten work procedures: A team of co-workers will develop ‘informal’ procedures and workarounds to deal with occasional situations that impact their productivity (sharing workstations, using each other’s e-mail program, etc). Some of these workarounds may contradict official policies. Users who follow such informal procedures usually act in good faith; they try to be helpful and practical to get the job done.

- Responsibility: Users are aware of password policies but continue to violate them because they do not expect to be held accountable for breaking the rules. “Everyone” regards the regulations as unrealistic.

- Management Privileges: Senior employees believe that they are too busy to be expected to follow what they perceive as petty rules (which often IT and InfoSec are known to disregard).

- Relevancy: Some users believe they and their systems are not important enough to merit serious attention from an attacker. They also believe that rigorous passwords are neither truly realistic nor necessary, and they do not see following information security policies as relevant to their job requirements and/or professional reputation.

Security, Perception vs. Reality

Another interesting self-contradiction that affected user perception of password security was password reuse. When questioned about the practice of resetting passwords to previous ones, a large number of administrative users and developers stated that whenever the system permitted it, they reset the new password to an older, familiar one. In some cases, administrators deliberately disabled password expiration policies to avoid the hustle. Clearly, this practice completely defeats any advantages associated with frequent password changes.

Chart 11: Changed passwords back to the original password

When we asked the users for their rationale for ignoring security policy directives and making this and other judgment calls, the answers clustered around these topics:

- Lack of account privacy affected general work habits and security: When users were regularly forced to write down their passwords because they lacked a tool to manage them properly, they also tended to justify keeping other sensitive information out in the open.

- Security mandates elicited strong emotional reactions: Users often spoke in emotional terms about unrealistic decrees, using terms like “smoke and mirrors,” “lip service,” and “window dressing.” Further, they said that they wanted their information to be secure and private, but at the same time, they had a fatalistic attitude toward security. That is, they felt resigned to accepting security breaches and privacy compromises.

- Inability to differentiate between security and privacy: Users didn’t distinguish between these concepts and mostly focused on the outcome of a security breach and its impact on their work product. In one example, an administrator did not consider the common practice of sharing passwords with a fellow administrator to be a privacy or security issue; when their password was discovered during the survey, they simply mitigated the damage by resetting the password and continuing the sharing practice.

- Multi-user applications and social interactions influenced information sharing: Collaborative work assignments and certain business processes promoted password sharing. Regarding account and password privacy, users working in a collaborative environment tended to have a more liberal and collective sense of account ownership.

- A few differences existed between home and business account management practices: The user’s lack of concern for account privacy did not depend on their work location. They were consistent in their practices, whether at home or at work. Remote users who connected via VPN were less concerned about the security of their work files because they considered the likelihood of someone hacking them at home minimal, even though their off-site network was much less secure (many had no firewalls or up-to-date anti-malware protection). Also, most users working from home did not consider themselves to be the potential target of an attack.

Conclusion

The survey results suggest that the widespread practice of users writing down passwords and keeping them in unsecured locations is a natural response to unrealistic security mandates. Users, in general, are concerned with productivity and view password management as an overhead and a dreaded chore.

Practical password security depends on the availability of password management and enforcement mechanisms. Any password policy must balance the benefits of protection and enforcement and minimize user impact. Without maintaining this careful balance, we risk users viewing policy mandates such as expiring passwords as tyrannical decrees that should be cleverly circumvented.

If a good personal and corporate security strategy depends on strong passwords—and few will argue that it does not—then the keystone of good password security is the establishment of an enterprise-wide solution that will either eliminate passwords or facilitate the management of the entire password’s life cycle via online, mobile, and offline access. Without such systems, the frustration of complex password demands might push even the calmest among us to the brink—or, as Milton Waddams would say:

“Well, Ok. But… that’s the last straw. And, I’m telling you, It’s not okay because if they lock me out again and force me to memorize another complex password, I’m I’ll, I’ll set the building on fire…”

Notes and References

Authentication in Internet Banking: A Lesson in Risk Management – FDIC (2007)

Uncovering Password Habits – Are Users’ Password Security Habits Improving?

The death of passwords is premature – Keeper (2016)

Microsoft admits expiring-password rules are useless – CNet (2019)

[1] Due to the sensitive nature of password surveys, conducting password storage searches should be planned and executed carefully and discreetly. Before conducting any searches, you should secure written approval from your IT, InfoSec, HR, and legal team. You should also coordinate all such activities with the local facilities team. Another good rule of thumb is to conduct all surveys in a team composed of representatives from HR and building security; this will eliminate the perception that some unknown individual is just pillaging and violating employees’ privacy after hours. Follow-up conversations with users regarding their password storage and recovery habits should be done privately in a non-threatening or confrontational manner. You should make it clear to the interviewee that their cooperation is appreciated, that this will not reflect poorly on their evaluation, and that the ultimate goal of this exercise is to improve both personal and corporate data security and privacy. A $20 gift certificate to Starbucks or another popular outlet would go a long way toward easing the tensions.

[2] C. Coombs, R. Dawes, and A. Tversky, Mathematical Psychology: an Elementary Introduction. Prentice-Hall Press, (1970). The study by Yan, Blackwell, Anderson, and Grant, “The Memorability and Security of Passwords-Some Empirical Results” (research paper, Cambridge University Computer Laboratory, 2001). And Miller, George A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63, 81-97.

[3] Schneier on Security Write Down Your Password (2005)

[4] Spafford, Eugene H. (1992). “Observations on reusable password choices” Proceedings of the 3rd Security Symposium. Usenix, September.

© Copyright 2019 Yaacov Apelbaum, All Rights Reserved.